Physics Behind Badminton

By Alvin, Danish and Ivan.

Physics behind the shuttlecock

#How the shuttlecock works

The badminton shuttlecock, also called a shuttle or birdie, is the projectile that is used in badminton. The shuttle makes badminton special and different from the rest of racket sports, where usually a ball is used as a projectile.

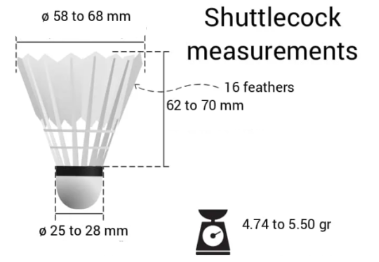

Shuttlecock’s average dimensions:

#The design of the shuttlecock

To understand the physics behind why the shuttlecock flips during flight, such that the cork points in the direction of the motion we first need to understand the terms centre of gravity and the pressure center.

The Centre of gravity is a point from which the weight of a body or system may be considered to act. It depends upon the mass distribution over the body. As the mass is mostly concentrated in the cork, the centre of gravity is located in the cork.

The pressure centre is the point within the object where the combined effect of the air resistance forces is considered to be concentrated. It's a way to simplify the complex interaction between the object and the air into a single point. In the case of a shuttlecock, it is located near the tip of the feathers (the skirt) where the cross-sectional area is the largest.

Cg - the centre of gravity

Cp - the centre of pressure

Cp - the centre of pressure

This image illustrates the flipping of the shuttlecock through the air.

Using the concepts of Cg and Cp we can explain the flipping of the shuttlecock. As the shuttlecock flies through the air, the force of drag exerted on the shuttlecock is mostly exerted at the centre of pressure, causing a negative acceleration (deceleration). We can consider the cork (where the Cg is located) and the skirt (where the Cp is located) as two separate bodies for the sake of calculating their acceleration separately.

Newton's second law states that Net force = mass acceleration . If we rearrange this equation to find the acceleration of a body we get Acceleration = Net Forcemass. So, The only force acting on the shuttlecock in the horizontal axis is aerodynamic drag. This means the net force will be equal to the drag force on the shuttlecock. As you just learnt the aerodynamic drag is experienced more at the centre of pressure. This means the net force (which will be negative as it is opposing the motion of the shuttlecock) will be greater at the centre of pressure (at the skirt) and hence the acceleration in the negative direction (deceleration) will also be greater for the skirt.

The centre of gravity is located at the cork of the shuttlecock, meaning most of the mass is concentrated there. Using newtons second law again we can see that a larger mass will result in less acceleration for a given amount of force. So overall this means that during flight a birdie will experience a much greater deceleration at its skirt as compared to the cork, this results in the skirt moving behind the cork and hence the head of the shuttlecock flips and the cork faces forwards.

#The physics behind the shuttlecock's rapid deceleration

The factors that contribute to the rapid deceleration

1. The shape of the skirt

The skirt has a cone like shape. The flared and curved shape of the skirt increases the surface area exposed to the oncoming air. A larger surface area means more contact between the shuttlecock and the air molecules, resulting in increased drag force. As the shuttlecock moves through the air, the larger surface area of the skirt generates more friction and resistance, causing greater deceleration.

Once again, using newtons second law a = Fm, we can see that a greater negative drag force, will result in a greater negative acceleration, which is simply a greater deceleration.

2. The spin on the shuttlecock

Shuttles are not exactly symmetric with respect to their axis because feathers are placed one over another. This asymmetry also exists for plastic models, and it implies that a shuttlecock rotates around its axis when placed into an air flow.

Most shuttlecocks are constructed so that they have a natural counterclockwise spin as seen by the hitter when the shuttle cock is moving away from him/ her. This is due to the overlapping of the feathers, which creates an asymmetrical shape. This “natural” spin stabilizes the shuttle cock while it flies. You can observe this spin by dropping the shuttle cock from a raised platform, e.g. a balcony.

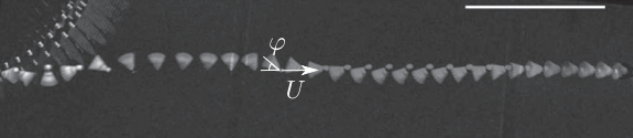

The rotational velocity Ω is measured as a function of the projectile speed U, as shown in the graph below. The graph reveals a linear correlation between R Ω and U, and differences between plastic and feather rotational velocities. Where the slope of the linear trend is equal to 0.02 for the plastic shuttlecock, the one for the feathered projectile is twice as large.

This spin across the central axis of the shuttle cock gets faster as shuttle cock travels faster. When the shuttle cock slows down, so does the spinning and it becomes less stable.

So far, this “natural” spin is present simply through the shuttle cock construction and is not due to player intervention.

Until a certain speed is reached the spin of the shuttle cock has little effect on its drag coefficient but simply stabilizes the shuttle cock much like a spinning top. Once the spinning goes over a threshold, however, the centrifugal force that it exerts on the shuttle cock pushes the “skirt” outwards thus increasing the cross sectional area of the skirt and hence drag, leading to a significantly faster deceleration of the shuttle cock.

3. The porosity of the skirt

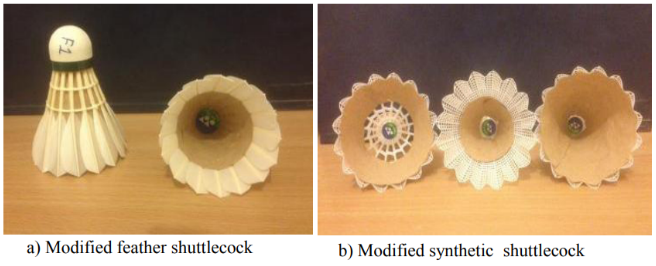

The porosity of the shuttlecock's skirt, referring to the presence of small holes or gaps in the material, also plays a role in generating drag force. To explain this we will take a look at an experiment conducted by researchers on the affect porosity of a shuttlecock has on the drag coefficient. It involved mounting shuttlecocks in the wind tunnel and measuring lift and drag forces.

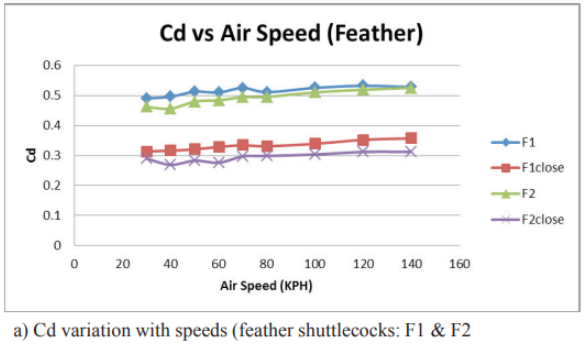

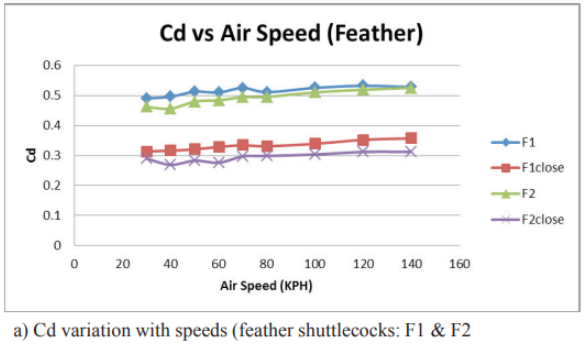

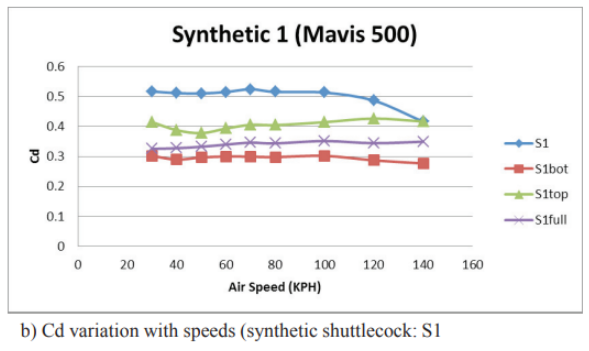

The shuttlecocks were tested at wind speed of 30, 40, 50, 60, 70, 80, 100, 120, 140 km/h. Feather shuttlecocks were modified by having the gaps at the skirt based closed. Synthetic shuttlecocks were modified by having the base gaps closed, skirt gaps closed, and the whole skirt section closed. This is to investigate the effect of gaps in each section of synthetic shuttlecocks.

The drag coefficients of all shuttlecocks (modified and unmodified) used in this study were plotted as a function of wind speeds.

Key:

F1 - Feather 1 (unmodified)

F1 close - The same shuttlecock with the base gap closed (image above)

Same goes for “F2” and “F2 close”

F1 - Feather 1 (unmodified)

F1 close - The same shuttlecock with the base gap closed (image above)

Same goes for “F2” and “F2 close”

S1 - Synthetic 1 (unmodified)

S1 bot - the same shuttlecock with the base gap closed

S1 top - the same shuttlecock with the top part of the skirt covered (further from the cork)

S1 full - the same shuttlecock with the entire skirt covered

S1 bot - the same shuttlecock with the base gap closed

S1 top - the same shuttlecock with the top part of the skirt covered (further from the cork)

S1 full - the same shuttlecock with the entire skirt covered

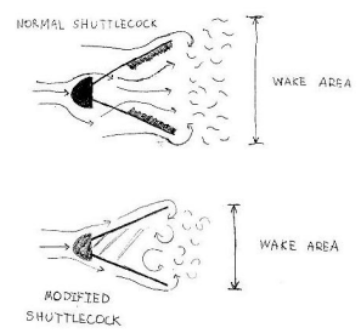

In order to explain how decreasing the air bleed can reduce drag, the wake region was considered. It was believed that the air flowing through the gap prevented the air flowing around the outside of the skirt to recirculate back into the blockage region which would cause the recirculation to occur further downstream and would expand outward, effectively increasing the wake area behind the shuttlecock.

The opening at the end that allows the flow to recirculate back in has a strong influence on the drag characteristic. Without it, greater wake area is bound to occur and thus greater drag. The wake is an area of disturbed airflow that forms due to the object's passage. The swirling air molecules in the wake can exert pressure on the object, pulling against its motion and slowing it down.

So in conclusion, greater porosity in a shuttlecock help increase its aerodynamic drag. By effectively enlarging the wake region, low air pressure is created to pull the shuttlecock backwards, dramatically reducing its speed. This gives the players enough time to react to shots with high acceleration such as a drive or smash.

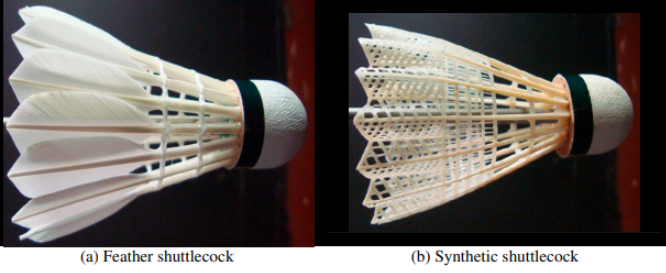

#The 2 types of shuttlecocks

The two types of shuttlecock are the feathered shuttle and the synthetic/nylon shuttle. As far as materials are concerned, the feathered shuttle is usually made of feathers from the left-wing of gooses, whereas the synthetic shuttle is usually made of synthetic materials (plastic)

Flight

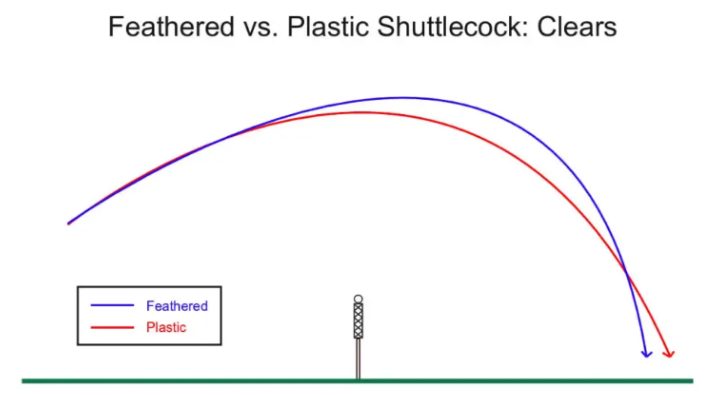

The flights of feathered and plastic may appear quite similar to amateur eyes due to the shuttlecock’s conical shape, however, intermediate to advanced players are able to discern the subtle differences, which make a big difference in gameplay.

Feathered shuttlecock: The trajectory of a feathered shuttlecock will resemble that of a parachute. You can imagine this as a feathered shuttlecock starting with a more standard arc, but then dropping off more steeply towards the end of its flight when it is falling.

The trajectory of a feathered shuttlecock is influenced by its construction of 16 individual overlaid feathers. Immediately after a hit, a feathered shuttlecock will experience faster acceleration as the feathers do not deform as much as plastic shuttlecocks do. Deformation refers to how much the shuttlecock’s composition is forcibly changed from its natural state. However, as more drag is imparted on a feathered shuttlecock throughout its flight, a feathered shuttlecock will experience a faster deceleration than a plastic shuttlecock, resulting in a sharper drop.

With a feathered shuttlecock, players are able to achieve higher clears to the back of an opponent’s court with a lower risk of it crossing the back line, given the steeper drop at the end of its flight. Additionally, players who hit drop shots from their backcourt can deliver drops closer to the net, given the faster deceleration of the shuttlecock.

Plastic shuttlecock: the trajectory of a plastic shuttlecock will take on more of a normal parabola, which are symmetric in nature, however, they are still highly asymmetrical.

The reason behind a plastic shuttlecock’s trajectory is also embedded in its construction. A plastic shuttlecock typically has a skirt that is made of one continuous piece of material. The impact of this design causes less acceleration upon hit, due to higher deformation of the skirt, but also experiences a steadier deceleration throughout its flight due to a relatively smaller drag effect.

As a result, a plastic shuttlecock’s flight will travel further but flatter than a feathered shuttlecock’s flight, when hit by the same stroke and power.

#Other properties

- Durability: Feather shuttlecocks are generally less durable than plastic ones. The delicate feathers can break or become damaged more easily, particularly with heavy or powerful shots. Plastic shuttlecocks, being made of synthetic materials, are more resilient and can withstand more intense gameplay without significant damage.

- Cost: Feather shuttlecocks are typically more expensive than plastic shuttlecocks. Feathers are a natural material that requires careful selection and processing, making feather shuttlecocks higher in price. Plastic shuttlecocks, being mass-produced and made of synthetic materials, are generally more affordable.

- Feel and Sound: Feather shuttlecocks are known for their distinct feel and sound when struck. The interaction between the feathers and racket strings creates a unique sensation and audible feedback upon impact. Plastic shuttlecocks have a different feel and sound due to their solid construction, which can be perceived as slightly harder and louder.

#Tennis Ball VS Shuttlecock

Air resistance:

The air resistance experienced by a shuttlecock and a tennis ball are very different due to their contrasting shapes and designs. A shuttlecock, with its conical skirt and feather or synthetic material, encounters extremely high air resistance as we discussed earlier. The large surface area, creates considerable drag, causing it to decelerate rapidly during flight. On the other hand, a tennis ball, with its spherical shape and smoother surface, experiences less air resistance. The streamlined design of the ball allows it to move through the air more easily, resulting in lower drag forces compared to a shuttlecock.

The air resistance experienced by a shuttlecock and a tennis ball are very different due to their contrasting shapes and designs. A shuttlecock, with its conical skirt and feather or synthetic material, encounters extremely high air resistance as we discussed earlier. The large surface area, creates considerable drag, causing it to decelerate rapidly during flight. On the other hand, a tennis ball, with its spherical shape and smoother surface, experiences less air resistance. The streamlined design of the ball allows it to move through the air more easily, resulting in lower drag forces compared to a shuttlecock.

Top Speed:

Shuttlecock: The top speed of a shuttlecock hit during a badminton game can reach impressive speeds. Professional players can generate speeds of up to 200 miles per hour (around 322 kilometers per hour) with powerful smashes. However, average speeds during regular gameplay typically range between 150 to 180 miles per hour (240 to 290 kilometers per hour).

Shuttlecock: The top speed of a shuttlecock hit during a badminton game can reach impressive speeds. Professional players can generate speeds of up to 200 miles per hour (around 322 kilometers per hour) with powerful smashes. However, average speeds during regular gameplay typically range between 150 to 180 miles per hour (240 to 290 kilometers per hour).

Tennis Ball:

The top speed of a tennis ball can also be quite high, particularly when hit by professional tennis players using powerful strokes. The fastest recorded tennis serve reached approximately 163.7 miles per hour (263.4 kilometers per hour) by Samuel Groth in 2012. Generally, professional players can hit groundstrokes and serves with speeds ranging from 70 to 130 miles per hour (110 to 210 kilometers per hour).

The top speed of a tennis ball can also be quite high, particularly when hit by professional tennis players using powerful strokes. The fastest recorded tennis serve reached approximately 163.7 miles per hour (263.4 kilometers per hour) by Samuel Groth in 2012. Generally, professional players can hit groundstrokes and serves with speeds ranging from 70 to 130 miles per hour (110 to 210 kilometers per hour).

Trajectories:

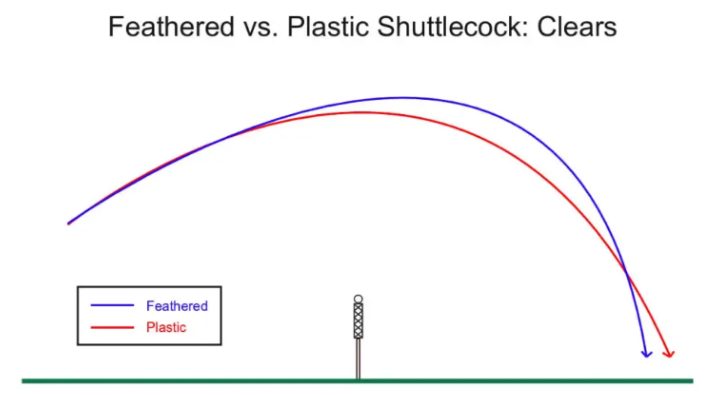

As shown in the images the parabola of a shuttlecock is asymmetric. The image on the right shows a shuttlecock parabola vs a tennis ball parabola launched at the same velocity and angle.

As shown in the images the parabola of a shuttlecock is asymmetric. The image on the right shows a shuttlecock parabola vs a tennis ball parabola launched at the same velocity and angle.

When we study projectile motion at the high school level we normally completely ignore air resistance and assume that the x-component of velocity remains constant throughout the projectile, and that the only force acting on the object is gravity. However, in real-life we know that air resistance will cause a deceleration in the x-axis too, and hence most real world projectiles are not completely symmetrical. In the case of a shuttlecock, the negative acceleration in the x-axis is extremely large (due to its unique design) and therefore causes a huge loss in horizontal velocity, resulting in the huge drop seen in the projectile. When compared to the tennis ball trajectory we can see that the tennis ball has much less negative acceleration in the x-axis and therefore has a more symmetrical projectile similar to the ones we study in high school.

The Physics Behind Rackets

Design:

Badminton rackets are typically lightweight pieces of equipment designed to allow for agile swings and the flexibility to produce various shots, including serves, smashes, drop shots, net shots, etc. There is no universal standard for all badminton rackets, and the aspects of a badminton racket are solely based on one’s habits and personal preferences. Throughout this page, I will be discussing the different aspects of a badminton racket and how they affect a player’s performance. I will be covering the physics behind a badminton racket, such as the materials used to create a racket, how the tension in the strings affects the shots, its relation to momentum, and finally sweet spots.

Badminton rackets are typically lightweight pieces of equipment designed to allow for agile swings and the flexibility to produce various shots, including serves, smashes, drop shots, net shots, etc. There is no universal standard for all badminton rackets, and the aspects of a badminton racket are solely based on one’s habits and personal preferences. Throughout this page, I will be discussing the different aspects of a badminton racket and how they affect a player’s performance. I will be covering the physics behind a badminton racket, such as the materials used to create a racket, how the tension in the strings affects the shots, its relation to momentum, and finally sweet spots.

Components:

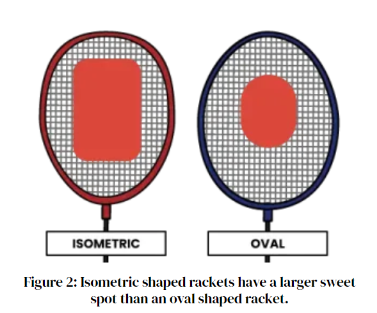

- Head: The area that surrounds the string area. Comes in 2 shapes: Isometric and Oval. The shape of the head alters the area of the sweet spot.

- Shaft: Connects the handle to the head.

- String Area: The netted part of the racket that deflects the shuttlecock upon contact. The cross strings alter the tension on the racket.

- Handle: Bottom-most part, allows for the handling, gripping, as well as controlling of the racket.

- Frame: The entire body of the racket.

- Throat: Supports the head by providing a steady base

Materials Used:

- Racket Frame

- Usually composed of aluminum and graphite, which are known for being lightweight materials.

- The “heavier” rackets are not made of different materials, they’re simply composed of more graphite/aluminum

- String

- Made of nylon, a durable and long-lasting material.

- Thicker nylon strings allow for more control and durability by holding more tension, but require more power from the player.

- Thinner nylon strings allow for more power by allowing for a greater reaction force. As the shuttle hits the strings, they stretch and propel the shuttle forward.

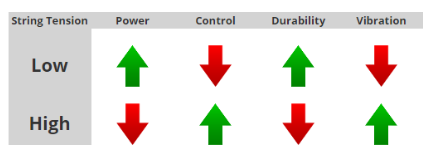

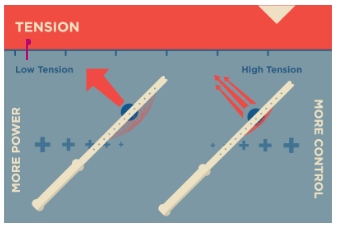

Tension of Racket:

The tension of the racket is crucial in badminton as the elasticity and flexibility of the strings both contribute to the velocity and handling of the shot. Different tensions of strings provide different repulsion power, which is defined by how the string assists in pushing the shuttle forward. Lower tension in the strings provides more repulsion, as their elasticity develops a tendency to stretch and propel the shuttle forward. (Admin, 2023). Higher tension in the strings provides more control, as the stiff strings provide less repulsion force, power is required from the player to compensate.

The tension of the racket is crucial in badminton as the elasticity and flexibility of the strings both contribute to the velocity and handling of the shot. Different tensions of strings provide different repulsion power, which is defined by how the string assists in pushing the shuttle forward. Lower tension in the strings provides more repulsion, as their elasticity develops a tendency to stretch and propel the shuttle forward. (Admin, 2023). Higher tension in the strings provides more control, as the stiff strings provide less repulsion force, power is required from the player to compensate.

Sweet Spots:

The sweet spot of a racket is the area on the strings that allows for the maximum impact, best sound, and least vibration when hit. When the shuttle strikes the sweet spot, it absorbs the maximum amount of forward momentum and thus producing the most power in return. This is because the closer to the sweet spot, the less energy transferred to the shuttle is lost, allowing the racket to provide the most kinetic energy back to the shuttle. Whereas hitting farther away from the sweet spot results in more energy given to the racket, and less kinetic energy is given to the shuttle in return. Sweet spots are usually located above the center of the string area. Factors that affect the area of the sweet spot are the shape of the frame and string tension.

The sweet spot of a racket is the area on the strings that allows for the maximum impact, best sound, and least vibration when hit. When the shuttle strikes the sweet spot, it absorbs the maximum amount of forward momentum and thus producing the most power in return. This is because the closer to the sweet spot, the less energy transferred to the shuttle is lost, allowing the racket to provide the most kinetic energy back to the shuttle. Whereas hitting farther away from the sweet spot results in more energy given to the racket, and less kinetic energy is given to the shuttle in return. Sweet spots are usually located above the center of the string area. Factors that affect the area of the sweet spot are the shape of the frame and string tension.

Momentum & Weight:

- Law of Conservation of Momentum

- According to the Law of Conservation of Momentum, momentum is conserved as the shuttle gains kinetic energy by striking the racket. The momentum lost by the racket is equal to the momentum gained by the shuttle. As we swing the racket, the racket gains momentum and is then transferred to the shuttle.

- Weight

- It is believed that “the lighter the racket, the more manageable and maneuverable it is.” (Allen Pros, 2023). Players are able to swing it faster to achieve higher velocity.

- Some people prefer heavier rackets as it provides more power.

- P = mv, meaning that mass and velocity are proportional to momentum. To achieve the greatest momentum, either the mass velocity can be increased to increase momentum.

- Lighter rackets make it easier to achieve higher velocities, while the mass of heavier rackets naturally creates greater momentum upon contact.

Simulation